Diffracting the infrastructural underground

Which methods to use to study digital infrastructure? Best use cases are the principles for creating software which is used to build software, - that is, for production of the means of production.

The discussion of the Infrastructural Underground in last week’s letter merits a few remarks on some of the key components of the methodology of research it calls for. My method can be generally described as compositional case study research. This means that I compose my method freely borrowing from other disciplines to arrive at a unique interdisciplinary view of software, extending professional DevOps, which brings together the disciplines of software development and operations. Throughout my research I look at software case studies diffractively, effectively attempting a queer methodology for DevOps, to open a conversation about a more-than-human representation of the space of production that sees the negotiation of shared meanings topologically and immanently. The topological meaning of the diffractive approach implies that it considers the differences through the relationships between parts, rather than in fixed values. This enables the method to assume the Infrastructural Underground in all of its complexity and to think about it in a parsimonious way, favouring the patterns of connections and the associated relationships over any complexity of implementation. Karen Barad employs a diffractive approach in the intersection of quantum physics and gender studies and emphasises that diffraction looks not merely at the differences, but at the character of entanglement of a set of differences in the context of a specific case. ‘Diffraction, - Barad writes, - is a material practice for making a difference, for topologically reconfiguring connections’. (Barad, 2007: 381 and earlier on ACD) In this sense, casework is inseparable from doing the diffractive study of DevOps, however, the cases themselves appear contingent and elusive. Therefore, rather than using the compositional model to evaluate the associations between the case variables, I lay the case out topologically, to trace the path of inquiry through their relations, rather than definitive distances between points. Topological account helps me to describe software systems by establishing the case variables as spatially continuous entities, that are simultaneously present in the different facets of the complex domain under study. (My topological account is based on the summary provided by Lury et al., 2012: 21.) For example, the constellations of people and technologies within the continuous planes of relations – the market and the organisation – make it possible to grasp analytically via variables such as the requirements and project stages.

A case of Jira

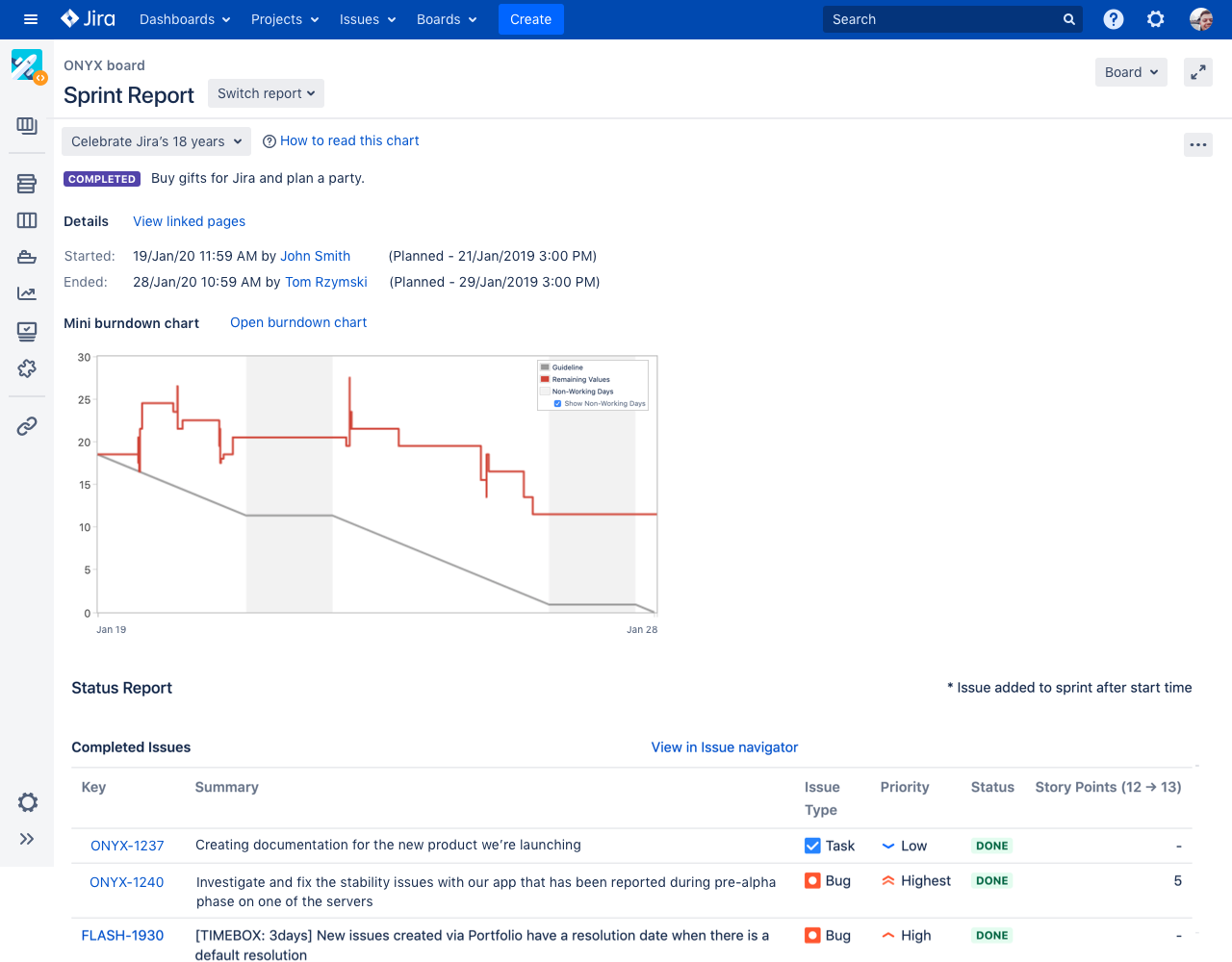

An appropriate case to look at with regards to diffraction is Atlassian Jira. Jira is a bug-tracking software based on support tickets, which came to the forefront of my interest because of its specific approach to knowledge. Throughout my work as a production team lead, I have used Jira as my day-to-day production tool for several years, thus gaining a detailed understanding of all of its intricate features. What intrigues me about Jira is its specific approach to written text and tight proximity to the epistemic infrastructure of the software system. Being predominantly focused on writing, Jira is different from traditional word processors because it is not a linear writing tool. Each issue or ticket created in it becomes a knowledge node of its own, allowing it to collect the information collaboratively within workgroups or communities of practice, and later create a variety of visualisations by applying filters to the associated information. In other words, Jira provides the means for creating an epistemic infrastructure, shared in the organisation and its technical resources by codifying and abstracting the knowledge captured by the collective use of its tickets. In this sense, it is a knowledge visualisation tool in an expanded sense, where visualisation is embedded in the apparatus of observation, capture and documentation. Jira’s visualisation works by converting aspects of problems into symbolic representations. In Jira, to use Barad's terms, the symbolic-material becoming of the problem is diffracted by cutting together-apart as a unified move. To begin with, Jira tickets are separated from the infrastructure that catalogues them, and then stitched back together according to the rules of their engagement and appear as search results - as can be seen, for example, in the Advanced Search results that pull together visualisation of a specific case based on Jira Query Language string (Fig.1). By clustering non-linear symbolic tickets around the nodes of the organisation's Infrastructural Underground, Jira reflects the queerness of the software system. Like the system itself, aggregation of support tickets focuses on differences and their effects, without ascribing a fixed notion of identity to any of them. This establishes software as a queer performative phenomenon, which is simultaneously a product and an event in the making, arising at every moment from its adjacent relations. As Fig. 2 demonstrates, Jira provides specific reports based on the abstract timeboxes, or sprints, which at every moment of their creation return results based on the activity of the associated community of practice (Fig. 2). On a wider scale of DevOps, Jira is present as a diffractive tool for understanding the Infrastructural Underground and the relations that underpin the software system in the process of its becoming.

References

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lury, Celia. 2021. Problem Spaces: How and Why Methodology Matters. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity Press.