Software as queer boundary-making

Where to draw a boundary in software between the product and process, the production and distribution, or human and non-human? Queer software performativity may give us new answers.

The practice of making boundaries occurs in places where the software components and human practices meet and enter into relations. The relations reveal where the boundary is drawn, how it is maintained and what activities it makes possible or necessary. Due to the inevitable conflicts of interest among the related parts, the relations change, making it necessary to renegotiate the boundaries. The boundary-making in this sense is performative in at least two meanings. First, humans perform when they produce and use the software. Second, there is the performance of the software itself, based on the performance of its components, such as database, environment, configuration and source code. In the former instance, the boundary is constituted by the human or institutional activities, and in the latter by the software system, which is no less active participant of production and exchange relations than the producers and users. Yet, the more nuanced account of boundary-making requires going beyond the human-machine divide, for which the queer view of software becomes indispensable.

Staying with the trouble

The two-way split in production is often referred to as dialectics, which means that the boundaries come as a result of struggle, or an antagonistic relation. Two forces, such as working and capitalist classes, in the foundational discussion of dialectics by Karl Marx, are decisively opposed, however, they simultaneously need one another to exist, therefore they labour to reproduce their relationship, despite its antagonism. (See the instructive discussion of class as a relation by literary scholar Sean O'Brien, 2020.)An alternative way to see boundary-making is queer, which here does not necessarily deal with sexuality, but is rather used to establish an affirmative mode of engagement, which does not have the same sense of antagonism as dialectics. Queering software affirms the contradictions that surround the conditions of its boundary-making, yet does not reconcile them, as positive dialectics aims to do, but rather develops their critique. Such a model of affirmative critique means that queer view aims to stay with the trouble, to use the term of the feminist scholar Donna Haraway, (Haraway, 2016) through creating a zone of negotiation, or problem space, to make the encounter between the contradictions happen and to gain a better grasp on where the boundaries are.

The dialectical and queer approaches are similar in the way that both are interested in relations, rather the relating entities. In the first instance, the workers and managers on the factory floor are interested in maintaining the boundary between the capital and the working class. As the cognitive scholar Edwin Hutchins observes, taking a car factory in terms of its organisational purpose, car production is not its primary outcome. Instead, the primary role of the organisational form could be to produce a specific social dependency schema, with cars being an additional benefit, more relevant to the model of the market involvement of the business, rather than to the organisation itself. (Hutchins, 2000: 225.) In other words, the organisation is a mechanism for reproducing the dialectical antagonism, or boundary-making, which is used by the value relation, which brings together human and non-human components of the software in the first place.

’The point is not merely to include nonhumans as well as humans as actors or agents of change, but rather to find ways to think about the nature of causality, origin, relationality, and change.’ - Karen Barad

Similarly, the queer approach also focuses on relations but has no preconceived ideas about what the phenomena are. Instead, it begins from the relations themselves, and by their careful evaluation arrives at the interpretation of the entities that participate in these relations. As the philosopher Karen Barad puts it, ‘the point is not merely to include nonhumans as well as humans as actors or agents of change, but rather to find ways to think about the nature of causality, origin, relationality, and change without taking these distinctions to be foundational or holding them in place.’ (Barad, 2011: 124.) In other words, the boundaries which continue to shift do not need to follow the pre-defined templates for boundary-making, such as the antagonistic reproduction of social class, as well as race, gender and their intersections. Instead, the queer affirmative critique expands the view to all natural and social entities to understand which differences matter in each specific case.

Diffractive method

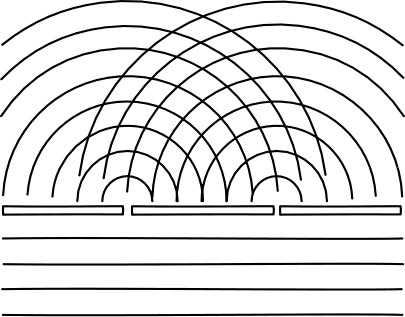

To examine such differences, Barad adopts the notion of diffraction. In its traditional use in optics, to diffract means to aim apart in different directions, and is often illustrated by the interference pattern formed by the waves when they come into contact with other waves or encounter obstructions. ‘When I drop two rocks in a pond simultaneously,’ - Barad writes, - ‘I get an overlapping of concentric circles. That is a diffraction pattern and what you see is that there is a reinforcing of waves. When two waves meet, crest to crest, they make a higher wave. But sometimes you get a crest meeting a trough, and they cancel out.’(Barad in Dolphijn and Tuin, 2012: 60.) This is the kind of many-to-many activity of boundary-making that the queer software performativity view can capture. While you can find a more thorough discussion of the diffractive method in other sources, such as this brilliant piece by cultural studies scholar and artist Sebastian De Line, the important methodological outcome at this moment is that diffraction allows the researcher to give up a fixed point of view and adopt multiple vantage points simultaneously. The affirmative style of such an approach lessens the pressure to make tough choices about the fixed boundaries within and around the software system. Some of such choices are how and why to split the human and non-human entities in a software system, whether to think of software as product vs. process or where production of software stops and its distribution begins.

To sum up, boundary-making is a crucial kind of involvement of software systems in the society’s fabric, however, its effects are often overlooked through the prevalent antagonistic, or dialectical idea of this involvement. Queering the boundary-making practice is productive because it does not limit the relation to two or other variables, and instead perceives the relations as a constantly changing flow, contingent in its complexity.

References

Barad, Karen. ‘Interview with Karen Barad.’ In Dolphijn, Rick, and Iris van der Tuin. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Open Humanities Press.

Barad, Karen. 2011. “Nature’s Queer Performativity.” Qui Parle 19 (2): 121–58.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures: Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hutchins, Edwin. 2000. Cognition in the Wild. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Marx After Growth #4 The Class Relation, Sean O’Brien.