The Nuts and Bolts of Creativity: How to Bring ‘Art’ Back into AI?

Is there ‘art’ in artificial intelligence? the mathematical poetry, the cyborgs, and the Solaris Ocean help to understand what creativity means in the context of the automatic production of culture.

As the machinic production of images, videos and text becomes more commonplace, the question that naturally arises is how much creativity such production involves and where exactly we look for it. Computation is the crucial component of a digital tool: using computation, the tool can layer abstractions functionally, in other words, it hides the code within the black boxes placed inside other black boxes, ad infinitum. In this sense, to understand what creativity means in such layered tools, we first need to find out how computation-based machines are different from mechanical ones. In her The ‘Art’ in Artificial Intelligence interview, the UC Berkeley scholar Nina Beguš starts by asking, how are we to think about computational machines? The core of automatic artistic production seems to appear purely formal, because the newly generated text arises from the pre-existing textual components, and not from any premeditated idea of what it should be about. This hints at the second question, - what is the AI-specific understanding of being creative?

The automatic production of text

Both terms art and artificial come from the same Latin root, which denotes craftsmanship and skill. Strictly speaking, art cannot be fake, because art by its definition is something that is produced artificially, in opposition to the phenomena occurring in nature, as a product of skill and mastery of specific tools and methods. Beguš relates the event of the automatic production of text by the machine with the practice of experimental literary movement, Oulipo. Short for Workshop of Potential Literature, Oulipo gathers writers and mathematicians interested in pushing the limits of what could be written by introducing the constraints into the writing method. Constraining the method prevents the role of the human in the writing loop from being the unique deciding factor, and in this sense, Oulipo’s practice is related to the automatic production of text in large language models (LLM). In LLM, creativity is similarly distributed - this time, across the infrastructure that consists of the database, the rules of access, and the decision-makers. As far as skill and technique go, art created by a machine is more artistic than anything produced by humans. The machine can be infinitely precise about the use of the tool, which is a measure of creativity in the art understood as the application of the method for the intentional production of something which cannot occur naturally.

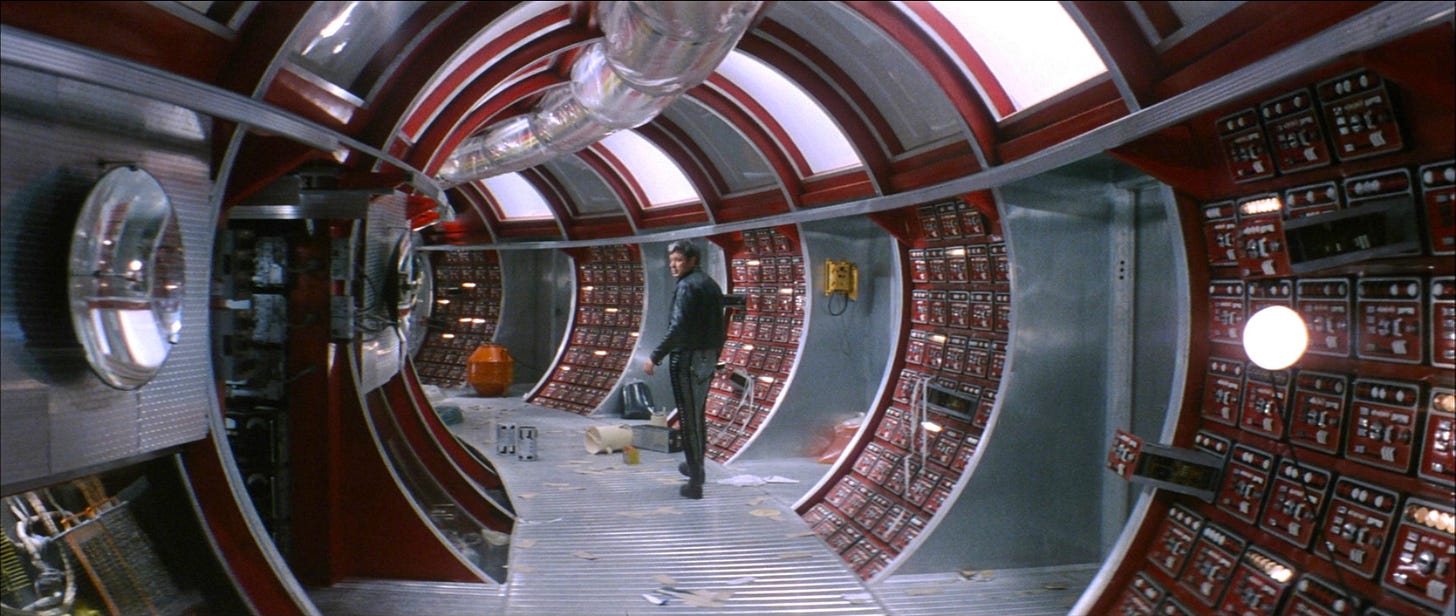

Through The Loops, @infiniteyay, distributed by @superchiefnft.

The cyborg is the author of AI poetry

At the same time, however, the machine is always interrupted by its complexity, or more precisely, the ability to black box, or to hide its complexity in the layers of abstraction. Such abstraction means that the large amounts of data, processed by the independently functioning components in different boxes, create a situation of uncertainty of functioning. This gives a new meaning to the idea of creativity, which is unique to artistic machines. To understand this, Beguš turns to A Cyborg Manifesto, a 1985 essay by a feminist theorist Donna Haraway. In Haraway, the cyborg is a living entity which is machinic-biological in terms of its material construction, and fictional-real in terms of its place in society. To Haraway, a description of such a compound cyborg is a tool for understanding how the various boundaries among the domains are created and maintained. (Haraway, 1991: 6.) Beguš, in turn, proposes the cyborg as the poet working across the four domains, - engineering, natural, fictional and social. In the event of automatic art production, the relations between the machinic-biological and the fictional-real are too complex to be controlled from any one of those domains and can only be nudged by human collaborators via text-based prompts. Since the prompts in themselves are expressed by text, they by default are unable to instruct the process in terms of its extra-linguistic aspects, including creativity. In this sense, the production of automatic art, Beguš notes, is doubly mechanical - not only when it is produced by computational means, but also when it is reduced to textual protocol of communication between the human and the machinic components.

Solaris Ocean

Machine creativity arises, therefore, not from experience, empathy, feeling or vibe, but develops through its resistance to the characteristically human view of the world. Since it cannot be subject to complete control from the side of human authors, it persists through the many miscommunications that constantly occur between the machinic, biological, fictional and real domains and the interruptions between the machine’s layers of computational abstraction. I conclude by adding a new analogy to the ones used by Beguš, - the Solaris Ocean, a central character of the science fiction novel Solaris by Stanisław Lem. In the novel, the Ocean is an alien and enigmatic entity which is capable of absorbing human experiences and manifesting the physical and psychological phenomena that interact with humans. Defying any attempts of understanding through conventional scientific methods, the consciousness of the ocean creates a change in humans who interact with it, challenging their ideas about memory, identity, perception and the nature of reality itself. In its specific treatment of human linguistic and aesthetic expression, the Solaris Ocean is creative in a way similar to the algorithmic poetry of Oulipo and Haraway’s cyborg.